Montgomery toys with the psychic space in which abjection is gendered, playfully prodding erotic hierarchies.

by Eileen G'Sell

A blonde ponytail waits alone on an unmade bed. A drilled hole in a blue box reveals a blinking eye. Pliers snap a wire hanger, the hanger’s corner trembling to the sound of windchimes. A cheese Danish is slowly punctured by a prim pointer finger.

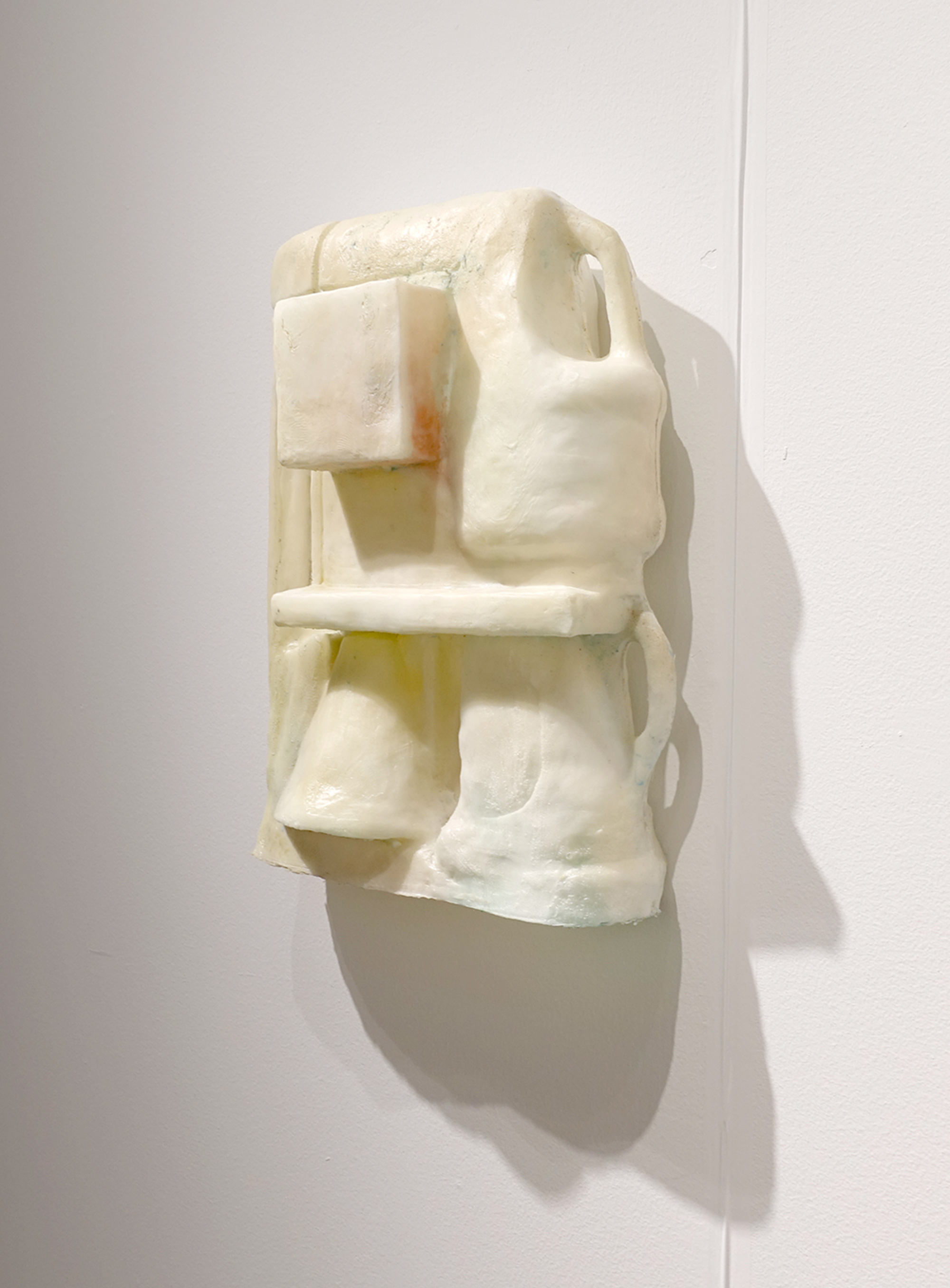

Welcome to the dreamscape of Virginia Lee Montgomery, whose recent videos charm — and alarm — in the New Museum’s Screens Series. A sculpture, video, and performance artist who has described her work as “a meta-structural argument for what it means for spirit to pass through form,” Montgomery marries an interest in the uncanny with a raptness toward the material. Error coins, dripping paint, Xeroxed cutouts of a smiling sphinx — the artist investigates each for its sensory properties, often referencing her professional history of diagramming ideas for corporate clientele.

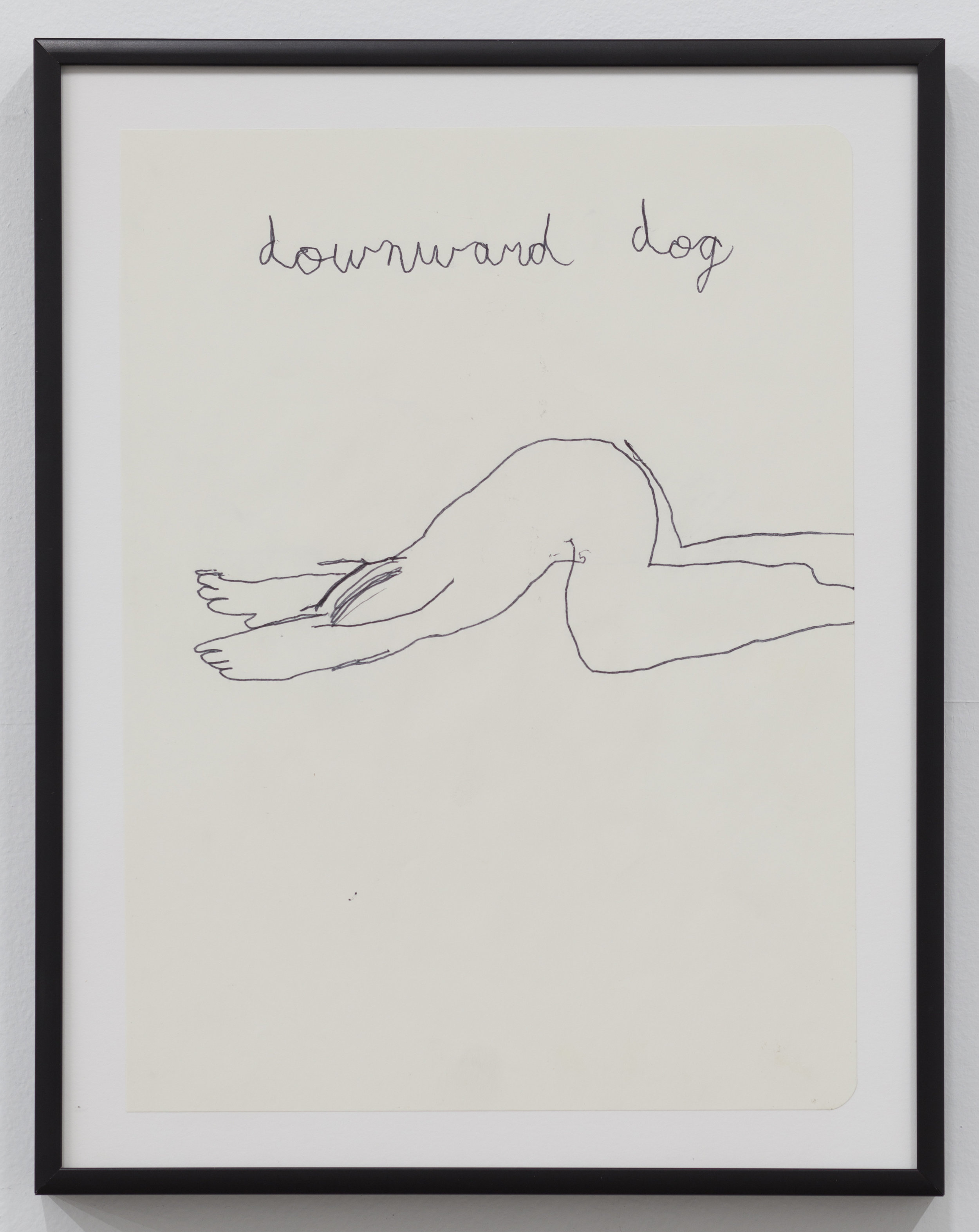

Upon this rather sterile stage of inorganic matter, the bodily and visceral make cheeky cameos. Disembodied hair, colorfully woven or tied with humble strings, becomes a metonym for a roving female subject. Honey — which can sometimes look like urine — slides over a cardboard surface. Danish frosting (or lonely semen?) dribbles down from a rainbow braid.

What results is an intermittent and very whimsical sense of the abject, less horrifying than it is subtly unnerving — a poke in the proverbial id, a pinky in the ear of consciousness. A concept explored by Julia Kristeva in her seminal study Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection(1980), the “abject” is typically linked to excretions and waste, what the body leaves behind to remain intact. “[A]s in true theater, without makeup or masks, refuse and corpses show me what I permanently thrust aside in order to live,” the French-Bulgarian philosopher writes. “These body fluids, this defilement, this shit are what life withstands, hardly and with difficulty, on the part of death. There, I am at the border of my condition as a living being.”

Whereas artists such as Cindy Sherman, Louise Bourgeois, and Sarah Lucas have explored the abject from an overtly feminist angle (as, after all, female bodily functions have always been more stigmatized than male), Montgomery toys with the psychic space in which abjection is gendered, playfully prodding erotic hierarchies in which men and women have been historically fixed. Power tools take on an unexpected feminine zest, leaving perfect circles wherever they go, everything a potential orifice to peek and reach through, often to the tune of birdsong.

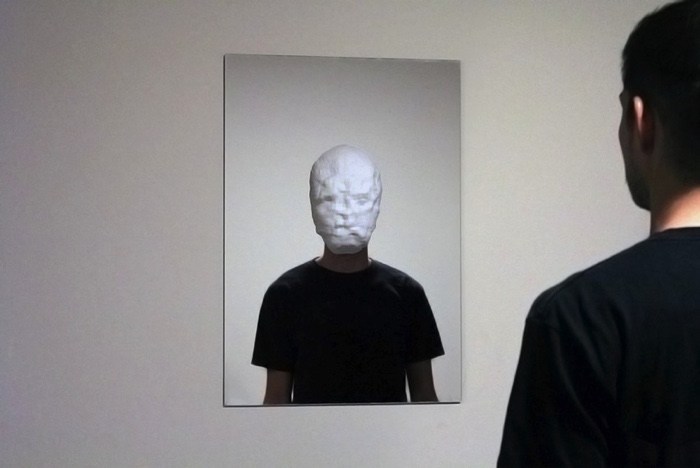

Montgomery is a woman who knows how to drill — literally, a Dewalt power tool in her pale, French-manicured hand. In Deep See (2017), the drill ruptures a 2-D seascape, a black-sleeved forearm entering to grasp at a human ponytail. In Pony Hotel (2018) shots of a sunny business suite are ruptured by close-ups of a silver bit suddenly entering a void. Cut Copy Sphinx (2018) montages one drill shot after another — each hole a possible frame for the artist’s own curious face. In Beyond Means(2017), pennies spin across a white surface, the sound of a drill whirring in the background. As a portal forms in a wall, a clear, gelatinous substance oozes from its edges, the artist’s by-now familiar hand invading to the sound of dripping water.

“Formally, I make work about circles — psychic or material ones, and what unexpectedly excretes out of open holes,” said Montgomery in a 2017 interview with She/Folk. “I can survey relationships between bodies, hierarchies between objects, genders, sounds, or forms, and thus allow forth a message to emerge from these intersecting realms of cognitive awareness and sensorial participation.”

Water Witching (2017), the longest video on display, invests these relationships with more conspicuously political significance. The spinning drill cuts to a corresponding graphic of a fearsome tornado, which segues into shots of melting glaciers, then to a montage of archival footage of women’s marches for reproductive rights. The hand-drawn hanger on a protest sign becomes an actual hanger relentlessly severed, then reshaped, by the artist’s fingers — as though carefully constructing some industrial talisman.

Whether bodies of water or bodies of women, cheese Danishes or a Dewalt drill, Montgomery perpetually tests the border between subject and object, matter and mind. “What is thing and what is theory?” her work seems to ask. What must we thrust aside to survive the tangible world?

Screens Series: Virginia Lee Montgomery, organized by Kate Wiener, continues at the New Museum (235 Bowery, Manhattan) through March 3.

Read More